Scenario Narrative

More democracy and economic progress

By 2032, the number and intensity of armed conflicts have decreased in the last decade as peaceful solutions are successfully pursued at the international level through a multi-faceted approach. The international community is taking responsibility for conflicts that stem from remnants of colonial history and, in some territories, solutions are being successfully found through international mediation. Countering the previous wave of undemocratic power shifts, many state governments around the world have been strengthening democratic institutions and procedures – moving higher up the scale of democracy – and regime violence is diminishing in many regions as a result. Economic development in third countries and global initiatives to reduce financial inequality (e.g. conditional debt cancellation) reduce the proportion of economic migrants within the flows of migration. In addition to further economic development, third countries now face lower wealth inequality and less poverty, while having better living standards and better access to health care. In transit countries , the economic situation and political stability improve and, as a result, part of the migrants decide to stay in these countries instead of continuing their travel to initially intended destination countries in Europe (or elsewhere). At the same time, regional solutions to improve economic and social conditions in countries or territories of origin reduce the overall pressure on transit countries.

Rising transparency and awareness for human rights

Supported by international jurisprudence, respect for human rights improves and minority rights are increasingly recognised globally. There are transnational (and properly enforceable) regulations to protect vulnerable groups, accompanied by technological and social developments that increase minorities’ awareness of their rights. Strong international civil society organisations collaborate to provide networks for minority groups and potential asylum seekers to report human rights violations and educate on international protection rights. Through the use of new technologies, oppression of minority groups is monitored and made transparent and is gradually receding from previous years. Mechanisms and technological infrastructure are in place to allow oppressed and vulnerable people to apply for international protection without increasing the risk of retaliatory punishment or forcing them to cross borders.

Consequences of climate change are recognised and addressed

Worsening climate impacts increase displacement and insecurity. In third countries, urbanisation is intensifying as – due to climate impacts – there is less arable land and opportunities for traditional farming, while greater urban economic capacities are driving population movements. Increasing environmental awareness is contributing to innovative approaches to irrigation and food distribution, including the improvement of regional structures to strengthen nutritional security. Climate change promotes a discussion that land and its use are inextricably linked to people’s identity and well-being; international regulations to reduce conflicts related to land appropriation follow. Technology reduces resource scarcity by improving the production and distribution of various goods, including food and water. International non-governmental organisations are pioneering a possible revision of international legal standards with regard to climate migrants fleeing countries with unsustainable living conditions. At the international level, there are more and more successful court cases regarding the recognition of climate change-induced displacement as a criterion for protection. A coalition of countries seeking regional cooperation is supporting climate change-induced refugees. Technology is used to protect people from the effects of natural disasters (e.g. predicting floods, droughts, etc.). Expanded fair trade campaigns have proven increasingly popular and new global regulatory frameworks are paying off, each helping to level the playing field for small agribusinesses in developing countries.

Digitalised asylum procedures

In 2032, a number of operational changes and supportive policies are shifting the approach to upholding international protection commitments. For example, asylum applications are often fully processed electronically and remotely (e.g. by conducting interviews online) in countries of origin. For asylum seekers with a positive asylum decision, safe pathways from the country of origin to the country of destination are ensured. These operational changes greatly speed up asylum procedures and result in fewer people engaging in irregular migration. Comprehensive information sharing between governments, agencies and some private actors enables improved services for asylum seekers, caseworkers and managers. If necessary, blockchain technology is used to prove identity and increase data protection. Occasional database inconsistencies and algorithm errors may lead to miscalculations and disruptive cyberattacks sometimes cause service outages. However, these are limited in number and scope. User-controlled private data enable reliable and faster artificial intelligence-assisted application processing. Organisations working in the field co-operate better with each other and provide information to speed up the processes of identity validation and travel history verification. In addition, biometric systems (facial, iris, voice and gait recognition) have become much more reliable as well as more portable and therefore more widely used in the identity verification process.

New opportunities for digital networks and platforms

Asylum seekers and other migrant groups are using digital technologies in a number of innovative ways. Regulated, mediated and trusted social media provide reliable information for various types of migrants and asylum seekers while respecting privacy by default. Protection of minority groups has been reinforced through successful social media campaigns, strategies and technologies that exist to debunk fake news and curb hate speech. At the same time, decentralised finance applications enable secure, global access to their own financial resources for migrants and asylum seekers. Virtual spaces blur the line between physical and digital life in the social and cultural spheres and enable families to live on a transnational basis. Many education and employment opportunities can be pursued from almost anywhere. Catching up on missed vocational training (during transit or due to conflict) is possible (in conjunction with open online courses) and has been broadly adopted among migrant communities.

Personas

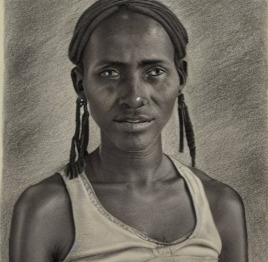

Disclaimer: The images used for the scenario personas are not real people.

Ahn

Ahn is a 22-year-old female, currently living in Hong Kong. Her main motivation for seeking international protection is to pursue better economic opportunities, but she has proof of being persecuted for online activities in support of political protests. She has extensive experience in IT, having worked as a developer of academic software and she has personal savings denominated in several Bitcoins. She has all of the relevant documentation she might need stored on a verifiable blockchain and she is aware of most application procedures through knowledge gained from internet research. Her only concerns are that her digital identification documents might not be accurately interpreted during application assessment and that her family might have to join her if they are persecuted for her behaviour and her seeking asylum.

Nage

Nage, a 25-year-old female from a small village in Ethiopia, is now located in Turkey and is considering applying for international protection. Her village became uninhabitable due to climate change and the money she earned as a farmer was no longer sufficient. She obtained only primary level education and can perform very little outside of agricultural work. She has been told to trust in the goodness of people during the asylum application process and that her story will be enough to convince any case worker of her need for international protection. She has a letter from her village chief attesting to her identity and she has multiple members of her family with her in Turkey who will also be applying for asylum. She has gained most of her knowledge about the process from her personal social media groups. Her biggest fear is that they will send her back and she is already feeling quite sick and weak.

Scenario Challenges

Geo-Political Challenges

- Disagreement on the adoption of conventions regarding the acceptance and treatment of ‘climate refugees’ complicates relations between nations on opposing sides of such a stance. In this scenario, cooperation without such conventions may imply complex legal arrangements that would affect authorities in the field of international protection.

- The economic development of traditional transit countries has a complicated impact on general migration and asylum-seeking. At the same time, we might observe increases in international protection applications (with more wealth enabling more families to afford the journey), and less economic migration as greater wealth lowers incentives to migrate.

- Legal and cultural differences, and non-complimentary socio-political goals make global cooperation very difficult, and hinder the development of binding agreements within global governance institutions like the United Nations.

- The new types of cooperation on international protection outlined in this scenario are intentionally vague, with details concerning bi-lateral or multilateral agreements are too specific for the scenario. This ambiguity does not erase the fact that any efforts between nations will remain burdened by unaddressed challenges (e.g. resettlement, aid, lodging and caretaking, security screening, etc.) .

Digitalisation and Data Challenges

- The use of artificial intelligence and automated systems imply a major shift in application processing operations (electronic processing, remote interviews). Additionally, this scenario calls for human oversight of automated systems, implying additional training and skills are needed to understand and properly assess automated system results.

- This scenario implies that various online platforms and technologies will be used to assist in verification of asylum applicant identities and outlines present day challenges that would have to be addressed for this scenario to be realized:

- Established information sharing agreements between governments and government entities

- Regulating social media to ensure information is trustworthy

- Securing private data and guarding against future cybersecurity issues and attacks.

Climate Change Challenges

- Since international organisations and some countries are expected to begin including climate change as a legitimate reason for granting international protection, this creates challenges with respect to requiring additional climate-related information in case processing and altering the criteria for assessing asylum applications.

- Additionally, if such an approach to ‘climate refugees’ is not universally approved (via a UN resolution for instance), then the asylum procedures may become complicated by unequal approaches.

- While this scenario presents a world in which there are concerted international efforts to confront climate change, it acknowledges that climate change effects are still developing and causing disruption and displacement in many places.